50 years after Kent State, Kent UCC’s people recall – and still play – key roles

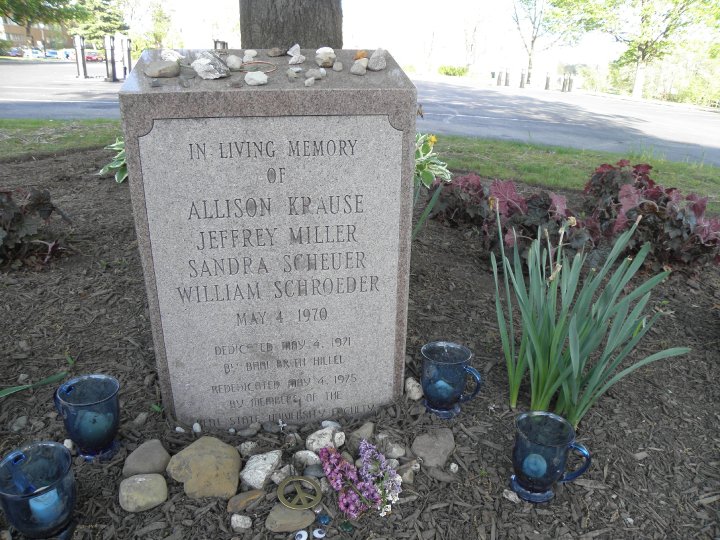

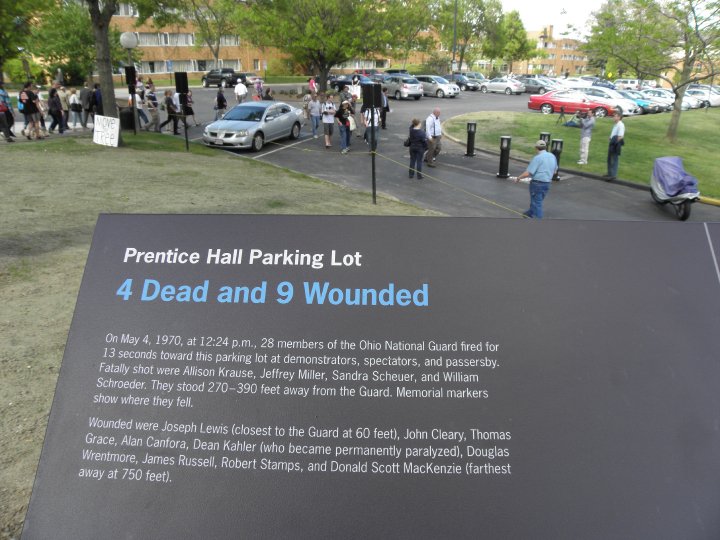

Alan Frank, a freshman on the swim team at Kent State University 50 years ago, was not an antiwar activist. Then he watched the Ohio National Guard fire military weapons into a crowd of unarmed students, killing four and wounding nine. “My reality changed forever,” he said.

David Hassler (right) was 6 years old and living in Kent, Ohio, the town surrounding the campus, when the shooting happened. Now he runs the university’s poetry center. His radio play, “May 4 Voices,” captures testimonials from students, soldiers and townspeople about the 1970 tragedy.

David Hassler (right) was 6 years old and living in Kent, Ohio, the town surrounding the campus, when the shooting happened. Now he runs the university’s poetry center. His radio play, “May 4 Voices,” captures testimonials from students, soldiers and townspeople about the 1970 tragedy.

When Kim Sebaly arrived at KSU as a professor in 1972, he joined a church next to campus and became intrigued by its history – which, he is convinced, prepared it to minister to a community in crisis.

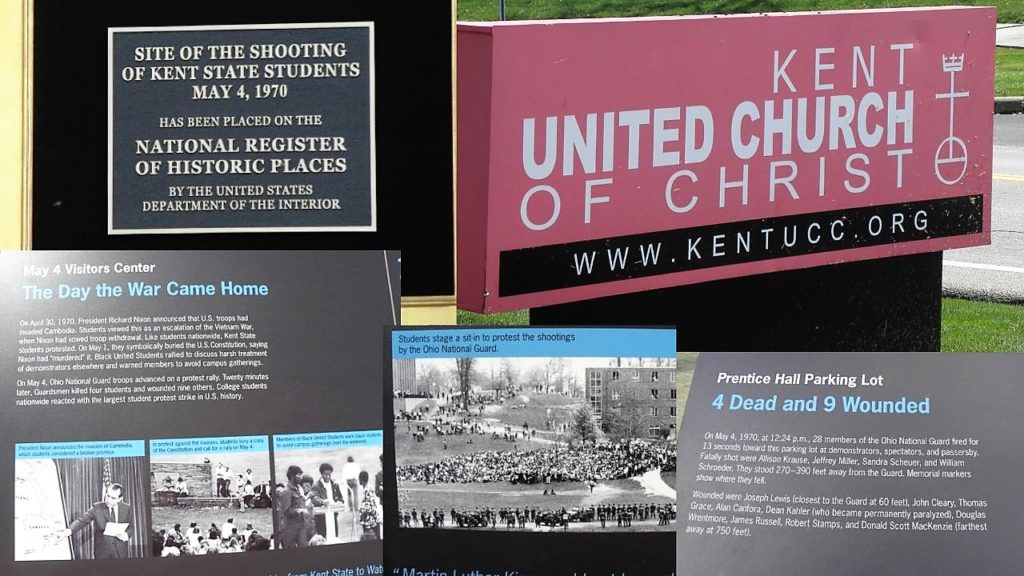

That church, Kent United Church of Christ, is where Alan Frank, David Hassler and Kim Sebaly are members today. It is a 9-minute walk from where the 13 victims lay in 1970. In the days after the violence, the church joined other congregations in hosting classes while the university was closed. And it welcomed citizens to voice their grief and anger in its sanctuary – in community forums as early as May 17 and in a choral requiem for the dead, performed June 3.

The church even has a connection to a moment when further death was prevented during the tragedy: One of its members at the time – a professor – persuaded angry students to stand down right after the shooting.

Today, Frank, Hassler and Sebaly are among many who preserve memories of events, which – like a similar shooting 10 days later at Jackson State University in Mississippi – shocked the world and figured heavily in the antiwar, social and racial justice movements of the time.

Spiritual nature of even talking about it

“We were to have had a huge worship service this Sunday in honor of May 4,” said the Rev. Amy Gopp, today’s senior pastor at Kent UCC. Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, causing the church, like most, to suspend in-person gatherings in favor of online ones. “We are now going to focus on peace as the theme of that worship service rather than on May 4 itself,” she said. “It’s just too much heartache to reopen on top of the pandemic.”

The coronavirus has caused the university, too, to modify what would have been a large 50th anniversary commemoration. Online opportunities have replaced dozens of in-person events and live appearances by public figures such as actors Jane Fonda and Tina Fey and musicians David Crosby, Graham Nash, Jerry Casale and Jesse Colin Young.

One of those – offered among the virtual commemorations and in public radio broadcasts nationwide – is Hassler’s play, with Fey among its vocal performers. It covers the turbulence leading up to May 4, including student protests of the U.S. invasion of Cambodia and the occupation of the campus by some 800 National Guard soldiers.

One of those – offered among the virtual commemorations and in public radio broadcasts nationwide – is Hassler’s play, with Fey among its vocal performers. It covers the turbulence leading up to May 4, including student protests of the U.S. invasion of Cambodia and the occupation of the campus by some 800 National Guard soldiers.

The play, which Hassler drew from 1,200 pages of oral history transcripts, debuted in 2010 as a live reading by student actors during 40-year observances – a year that Hassler sees as a spiritual turning point.

‘Silencing of this traumatic event’

“The number 40 in numerology is considered the ‘number for probation,'” Hassler said. “It is significant in all world religions and suggests a period of time after which a seismic shift in consciousness or resolution can happen – or not.”

Around 2010, university and townspeople “began to work together and talk more openly about the collective trauma our community experienced in new, productive, and healing ways,” Hassler said. “A kind of silence was broken within the larger community. I feel that I was one of the many instruments of this shift in energy and my work on the play was an instance of me being a conduit for this larger spiritual energy of our community.”

Hassler was not on campus when the shootings happened. His father, Donald Hassler II, a professor of English there for 48 years, was in a university cafeteria at the moment.

But May 4 memories are strong for the entire community. “I remember watching armored vehicles that I thought were tanks moving through our town, and I remember an Army helicopter landing where we played kickball, in a field just down the road from our house,” Hassler said. Too young to understand it fully, “I picked up on the anxiety of the adults around me and the fear and the confusion,” he said. “I remained receptive to that for years, growing up in this town, surrounded by the silencing of this traumatic event and felt the taboo and the difficulty of people even talking about it.”

‘They killed them!’

‘They killed them!’

Among those who couldn’t talk about it for years was Frank, the self-described jock who showed up at the demonstration site on May 4 with some buddies “to see what was going on, just kind of following the crowd.” “For the first 10 years, when people would ask me about Kent State, I found it impossible to talk about it, and I would end up crying,” he said.

One reason, he said, was the shock and unbelievability of it all. “We had just seen this 10 minutes of what I would call a circus: the students and the Guard throwing rocks back and forth from hundreds of feet away,” Frank said. “I don’t remember anyone getting hit. It was ridiculous. And then the same with tear gas canisters.”

When the soldiers took their rifles up a hill, turned in unison and shot into a crowd below, “we were laughing,” Frank said. “We thought, ‘They’re firing blanks!’ Then I remember this one guy screaming, ‘They killed them!’ I’m like, what? I walked to the top of the hill and saw the carnage.”

More carnage would have followed were it not for a member of Kent UCC – Frank’s father, Glenn Frank, a former Marine and a KSU geology professor at the time.

‘Would you please listen to me!‘

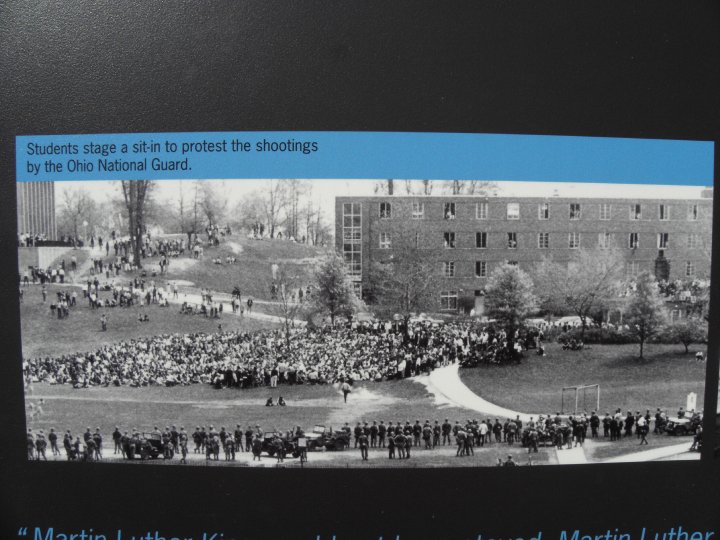

Not far from where ambulances had just carried away the dead and wounded, a crowd of defiant students had planted themselves opposite a line of soldiers (pictured above). Among the students was Alan Frank, converted in an instant from spectator to resister.

“There were probably at least 1,000 of us, just sitting there,” Frank said. “Everybody said, ‘If you’re going to shoot somebody, shoot me.’ All it would have taken, for me at least, would have been for somebody to stand up and say, ‘Hey, let’s get ’em.’ There would have been hundreds of people slaughtered.”

That’s when Professor Frank (pictured below) intervened. “I remember seeing my dad going back and forth between the Guard and the students,” Alan Frank said.

Audio of the professor’s plea to the students is preserved a website devoted to his May 4 role and his research in the years that followed. “I don’t care whether you’ve never listened to anyone before in your lives,” Glenn Frank shouted. “I am begging you right now: If you don’t disperse right now, they’re going to move in, and it can only be a slaughter. Would you please listen to me! Jesus Christ. I don’t want to be a part of this.”

Audio of the professor’s plea to the students is preserved a website devoted to his May 4 role and his research in the years that followed. “I don’t care whether you’ve never listened to anyone before in your lives,” Glenn Frank shouted. “I am begging you right now: If you don’t disperse right now, they’re going to move in, and it can only be a slaughter. Would you please listen to me! Jesus Christ. I don’t want to be a part of this.”

“Luckily, what he said helped all of us stand up and get away,” Alan Frank said.

The church engages the crisis

The university closed for six weeks. The shocked community was divided over who was responsible for the violence – students, accused of burning a Reserve Officer Training Corps building on campus and trashing the town in the days leading up to May 4, or officials who ordered such a heavy Guard occupation and armed soldiers with live ammunition.

Kent UCC became a venue to voice it all, as seen in documents collected by Sebaly. They include accounts of the performance of Cherubini’s “Requiem Mass in C Minor.” The community chorus and orchestra included more than 200 local people of varied opinions – students, faculty, staff, townspeople. Led by famous conductor Robert Shaw, it drew a crowd of 600, who rose in reverent silence at the end – just a month after the shooting. “For me, the requiem was that one brief moment in time when the community took a moment to look at itself and confess that it did not know what had happened, but that it was deeply grieving,” Sebaly said.

The documents also describe the May 17 forum and breakout groups at the church that drew 142 people to discuss “major problems which must be solved if the relationships between the community and the university were to be preserved and advanced” – and about 100 home meetings that followed to foster conversation.

“Church members provided a lot of leadership for the meetings,” Sebaly said. “Many of its members had deep crossover interests in the university.” Among them were Kent’s mayor, KSU’s president and the chair of its community relations committee. The Rev. Bill Laurie, pastor at the time, worked with them and others to help make the requiem and community forums happen – as well as a full-page newspaper message on academic freedom and responsibility.

Kent UCC was ready for crisis engagement not only because of its prominent members and activist roots – 19th-century abolitionist John Brown started his campaign while a member there – but because of thoughtful, intelligent, world-concerned preaching and teaching over the years, Sebaly said.

Still ‘felt deeply in our bones’

Gopp has inherited that legacy. She arrived as pastor in 2017, after years of global and ecumenical work. But she already knew the importance of May 4. Kent is her hometown. She was born almost exactly a year after the shootings.

“The effects of mass trauma change the lives of not only those directly impacted, but the entire community,” she said. “The collective consciousness of our beloved town has been forever marked by those tragic events. Kent UCC has been a witness and a participant in both the heartache and the healing.”

“The effects of mass trauma change the lives of not only those directly impacted, but the entire community,” she said. “The collective consciousness of our beloved town has been forever marked by those tragic events. Kent UCC has been a witness and a participant in both the heartache and the healing.”

The congregation still tries to instill hope and create spaces for healing, she said – such as a March concert for social justice performed at the church as part of this year’s commemorations, shortly before COVID-19 shut things down.

“While 50 years may seem a significant milestone, the tremendous grief experienced by the university, our congregation, our town and the entire country continues to be felt deeply in our bones,” Gopp said. “But the past five decades have also provided countless lessons for what peacemaking, empathy, forgiveness and healing entail.”

Violence backfires: ‘People come together‘

For eyewitness Alan Frank, those decades have included encounters with people who thought the shootings were justified. “It was not a shooting situation,” he said. “I tried to explain that to my friends’ parents who said the Guard should have shot more students. ‘You weren’t there,’ I told them. ‘You didn’t see it.'”

Since May 4, he has noticed repeatedly that violence meant to control people “has the opposite effect” – much as it did on him and that crowd of surviving students. “People see the injustice of what happened, and they say, OK, we’re going to resist,” Frank said. “Anytime the government has some kind of angry response, it backfires on them. People come together who wouldn’t have otherwise.”

(Photo of Glenn Frank used by permission: Kent State University News Service May 4 photographs. Kent State University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives.)

Related News

Love of Children Imagine Lab: Children and youth leaders gather to build connection, innovation in ministry

Love of Children is more than a team name at the United Church of Christ National Setting....

Read MoreYour generosity uplifts us: Request for Annual Fund donations

The church is called to be the church, and the mission of the United Church of Christ stays...

Read MoreDisaster preparedness workbook and webinars help churches for ‘when’ not ‘if’ they strike

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predictions for an above-normal...

Read More