Commentary: Time to give ourselves to the struggle until the end

Fifty years ago today, on February 1, 1968, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, two black sanitation workers in Memphis, Tenn., were crushed to death in the back of a garbage truck when a compactor malfunctioned. They were not the first to die in this brutal fashion. Two men died the same way four years earlier and the city refused to replace the failing equipment. These deaths brought attention to the horrible working conditions and meager wages of the 1,300 Black sanitation workers in Memphis.

Fifty years ago today, on February 1, 1968, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, two black sanitation workers in Memphis, Tenn., were crushed to death in the back of a garbage truck when a compactor malfunctioned. They were not the first to die in this brutal fashion. Two men died the same way four years earlier and the city refused to replace the failing equipment. These deaths brought attention to the horrible working conditions and meager wages of the 1,300 Black sanitation workers in Memphis.

Black sanitation workers earned an average of $1.80 per hour in 1968, such meager wages that 40 percent of workers were on welfare, and hundreds were forced to rely of food stamps to feed their families. There were no benefits, vacation, or pension. The mayor of Memphis at that time refused to repair or remove dilapidated equipment and would not pay overtime to workers forced to work late and extended hours. There was no dignity afforded to those in the service industry fifty years ago and sadly there is still no dignity afforded to those whose jobs enable the comfort of the masses today. Fifty years later, a living wage is still an aspiration for far too many hard working citizens. Fifty years later, adequate and equitable healthcare coverage still eludes too many. Fifty years later, there are still cities in America where people working two full time minimum wage jobs cannot afford adequate housing and food for their families. Fifty years later the working poor are still poor.

The Memphis Sanitation Strike did not begin with wide support from the churches or the black middle class. Privilege remains the enemy of liberation, no matter one’s race, gender, or ethnic origin. Within the week the local NAACP endorsed the strike and a few weeks later, after seeing Black sanitation workers tear-gassed and abused by violent police tactics as they marched to City Hall, the Black community mobilized and joined the workers’ fight. Soon after national attention was garnered and students from high schools and colleges, many of whom were white, came to Memphis to march with the workers. Trash piled up and racial hatred festered.

It is interesting to me that the oppressed and the oppressor do not share the same definition of nonviolence. To the oppressed, the right to protest one’s social condition without physical assault is nonviolent. However, the privileged often experience these protests as violent assaults, not because of bodily threats, but because comfort and conveniences are challenged.

In Memphis, the jails filled and protestor’s lives were threatened. And the garbage piled up.

The night before Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis, he spoke to the gathered crowd of sanitation workers and their allies. He reminded them, and us, “We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through.” (King, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” 217).

And here we are, fifty years later, still fighting for recognition of the basic humanity of the poor. In 2017, the city of Memphis voted to give $50,000 grants to each of the 14 surviving sanitation workers from the 1968 Strike, four of whom were still working on the garbage truck as recently as last year, and none of whom ever received a pension. The poor are still victimized and criminalized in a country where there is more than enough. The struggle is not done. The Poor People’s Campaign is not done! The fight for economic justice is not done! As Rev. Dr. King urged, we must give ourselves to this struggle until the end.

Much has been said about the rise of the so-called religious left of late, but one thing is for certain – people of faith are showing up all around the country to make their voices heard in response to policy attacks on immigrants, low-wage workers, people of color, LGBTQ individuals and more. Momentum is stirring in our nation’s capital this spring, as thousands of interfaith advocates plan to engage in advocacy through events such as Ecumenical Advocacy Days, the National Council of Churches (NCC) initiative, “Act Now: Unite to End Racism,” and the Poor People’s Campaign for Moral Revival.

April 4, on the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the National Council of Churches will gather hundreds of thousands of people on the National Mall to remember the past and to launch a comprehensive effort to end racism. The UCC, as one of the NCC’s 38 member communions, will be actively engaged in this project.

April 4, on the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the National Council of Churches will gather hundreds of thousands of people on the National Mall to remember the past and to launch a comprehensive effort to end racism. The UCC, as one of the NCC’s 38 member communions, will be actively engaged in this project.

The 2018 Ecumenical Advocacy Days, taking place April 20-23 in Washington, DC, is a weekend offering clergy and lay leaders an opportunity to worship and learn together, all while honing their advocacy and organizing skills. This year’s theme, “A World Uprooted: Responding to Migrants, Refugees and Displaced People,” is especially timely as our nation’s leaders continue to debate the fate of our nation’s immigrant and refugee policies.

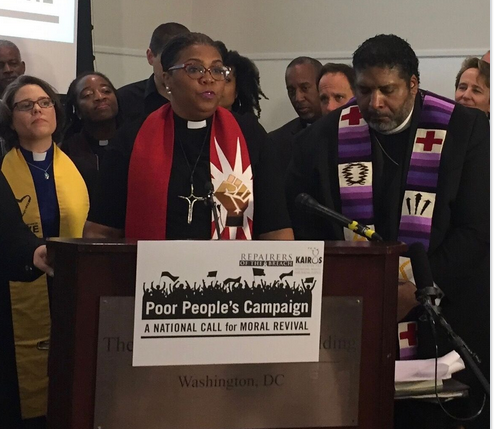

The Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival hopes to unite Americans across all races, creeds, religions, classes and to demand a moral agenda for the common good. Direct action and civil disobedience across 25 states will begin on Mother’s Day, leading up to a mass mobilization at the U.S. Capitol June 23.

Mark your calendars, and make plans to join us.

The Rev. Traci Blackmon is Executive Minister of Justice and Local Church Ministries, United Church of Christ

Related News

Peace Be With You…

“…And also with you” is the response on Sunday mornings and on occasions where the peace...

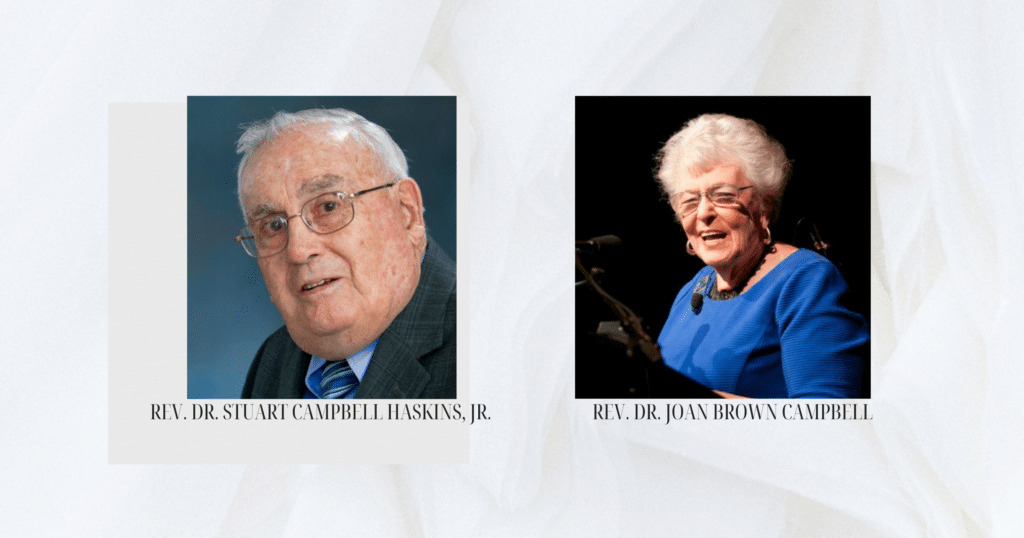

Read MoreBreaking barriers and forging loving partnerships: Two servants of God are remembered

This Eastertide, the United Church of Christ remembers the Rev. Dr. Joan Brown Campbell and...

Read MoreGetting down and dirty in the soil: Rural congregation discovers ‘life has the last word’

The Rev. Julia L. Brown has a love/hate relationship with this time of year. “I dislike...

Read More