FCC chair reveals proposed ‘digital discrimination’ rules at Parker Lecture

Disparities in broadband access and affordability are discrimination, regardless of intent, according to proposed rules that the Federal Communications Commission soon will vote on.

FCC chair Jessica Rosenworcel announced this to a roomful of digital justice advocates as she was delivering the 41st Annual Everett C. Parker Lecture, hosted by the United Church of Christ Media Justice Ministry, on Tuesday, Oct. 24.

Rosenworcel was honored by the UCC Media Justice Ministry alongside Sen. Tammy Duckworth, D-Ill., and Alisa Valentin of the National Urban League for their work toward justice and equity in communications.

The long-time FCC commissioner and first-ever woman to serve as the permanent head of the agency spoke about efforts to define “digital discrimination” to the morning gathering inside First Congregational UCC of Washington, D.C.

Intent vs. impact

The key part of that process, Rosenworcel told the crowd, was the creation of a task force that held listening sessions with stakeholders and communities throughout the nation. This came from a mandate given to the FCC by Congress, through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, to adopt rules to “facilitate equal access” to broadband internet services in order to prevent “digital discrimination of access based on income level, race, ethnicity, color, religion or national origin,” Rosenworcel explained.

Since the agency had to adopt these rules within a specified timeframe — the deadline is Nov. 15 — the FCC task force quickly got to work gathering input from communities, state, local and tribal governments, digital equity advocates, service providers and their various experiences with the telecommunications industry, according to Rosenworcel. “They made clear that the first question we needed to answer in crafting our rules — well, it’s how do you define ‘digital discrimination’?”

She said that there was near-universal agreement that digital discrimination should include business practices that were the result of “discriminatory intent.” However, Rosenworcel noted that there wasn’t a clear consensus on whether the definition should include practices that have discriminatory effects — even if they’re not intentional.

“So, we took it all in,” she said. “We read the record from front to back. We reviewed the listening sessions. We studied the statute and, specifically, the fact that the explicit goal of these rules is to ‘facilitate equal access to broadband.’ Let me repeat that: to facilitate equal access to broadband.

“And we realized that the definition of digital discrimination has to include disparate impact.”

‘Landmark legislation’

Thus, Rosenworcel has drafted rules that define digital discrimination as any policies or business practices that cause disparities in access.

The Congressional mandate from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law is “making history,” Rosenworcel said, even beyond the enormous potential for broadband affordability and deployment laid out in the legislation.

She pointed to how the law brought about the FCC’s Affordable Connectivity Program, “the largest broadband affordability program in our nation’s history,” which already has more than 21 million households enrolled. In addition, the bill “also created the largest broadband deployment effort ever, with the $42.5 billion distributed by the Department of Commerce for high-speed infrastructure,” she added.

Even so, Rosenworcel maintained that its significance went well beyond the funding. “You could strip out that $42.5 billion, and this would still be landmark legislation for digital equity.”

Why?

“Folks from across the ideological spectrum put into law that broadband is essential; that the digital divide disproportionately effects people of color, low-income communities and rural areas; and that this divide is hurting the economic competitiveness of the United States,” Rosenworcel said.

“Feels appropriate to say ‘Amen,’” she added, glancing around the sacred space with a smile, and the gathering responded accordingly.

Prison phone rates

While much of the morning’s focus was on the newly proposed digital discrimination rules, Rosenworcel and the other honorees were also praised for the impact they’ve had on other media justice concerns.

At the forefront of that was the passage of legislation in December 2022 to limit communications service rates for those who are incarcerated in prisons, jails and similar facilities.

Duckworth was a champion of the law, known as the Martha Wright-Reed Act.

“For years, one phone call — one phone call — from a correctional facility could cost about as much as a monthly phone plan,” Duckworth said after receiving the Everett C. Parker Award. “It prevented too many children from being able to hear the comfort of their parents’ voices. It kept too many spouses from being able to say a simple ‘I am here for you’ to their partners, even from a hundred miles away. And, let’s just be clear: when unjust and unreasonable communications rates cut off an incarcerated person from vital connections, the harm extends far beyond that single family.”

This ripple effect is why communications policy is deeply important to justice advocates, as noted by Valentin, who received the Donald H. McGannon Award for her contributions to diversity and equity in such policymaking.

“To many in this room, policy isn’t just a job; it’s personal,” she said. “At least, it is to me.”

“We’re all here today because we believe in a very simple truth: that our fight for inclusivity has to, well, be inclusive of every sector of our modern world, from voting reform to educational reform, from environmental justice to — crucially — telecommunications justice,” said Duckworth.

Parker’s legacy

Both Duckworth and Rosenworcel noted that much of this justice work was built on the efforts of the late Rev. Everett Parker, after whom the lecture is named.

“You can also see Dr. Parker’s legacy in every word, every line, of this new law,” Duckworth said.

Rosenworcel spoke about the foresight the UCC Media Justice Ministry had in speaking about issues such as “electronic redlining” when the internet was in its infancy.

“They called it ‘electronic redlining’ because UCC Media Justice and their allies saw patterns in the deployment of advanced communications that resembled old-school redlining,” she said. “… You predicted the digital divide before the digital revolution was even underway. That is stunning.”

And much of that visionary advocacy, which continues today, is due to the foundations laid by Parker.

“He did more than just tear down barriers of discrimination in the broadcasting industry,” Rosenworcel said. “He changed the way our policies are made. For a long time, the only people who could participate in the FCC’s proceedings were those we regulated. They had a clear economic stake in what we were considering, and that was the end of the story.

“But he rewrote it. Because a court embraced his argument that citizens have a right to be heard before federal agencies like the FCC. That might seem obvious now, but it was revolutionary back then.

“And it changed the FCC for the better.”

Content on ucc.org is copyrighted by the National Setting of the United Church of Christ and may be only shared according to the guidelines outlined here.

Related News

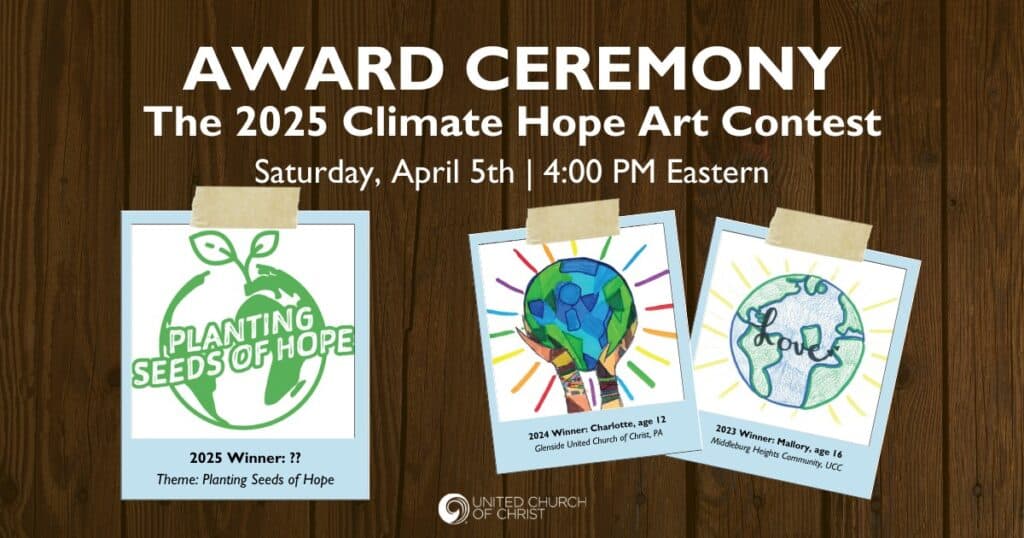

2025 Climate Hope Art Contest award winners plant seeds of hope

The celebration of the 2025 Climate Hope Art Contest for children and youth of the United...

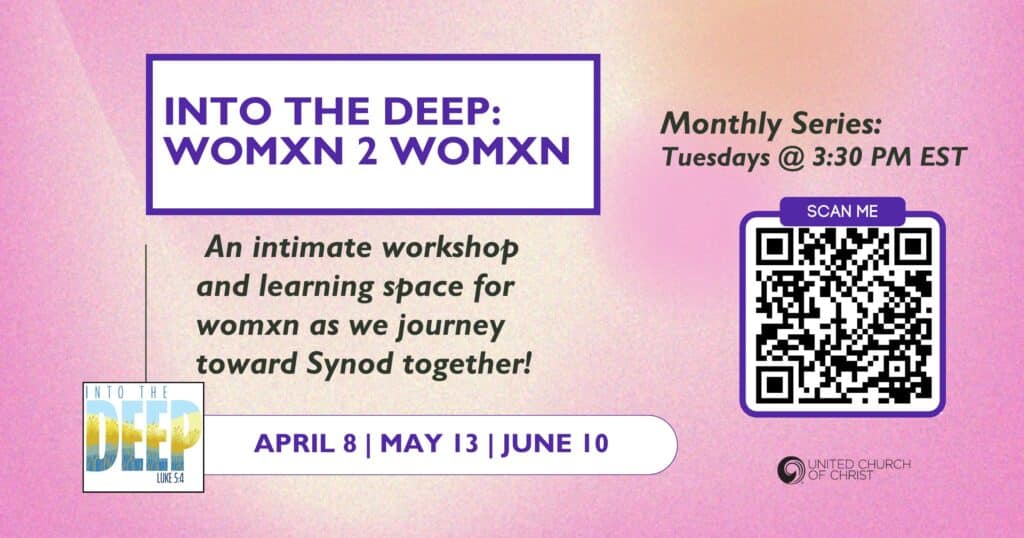

Read More‘Not your typical webinar’: Womxn 2 Womxn series aims to foster community

As the church works towards gathering this summer at General Synod 35 in Kansas City,...

Read MoreThompson to bring a ‘prophetic and pastoral’ message to Synod: ‘We are not all the same, but still one body’

On Sunday, July 13, the Rev. Dr. Karen Georgia Thompson will take the stage at the 35th...

Read More