Speaking their names: D.C. church remembering enslaved people who worked this land

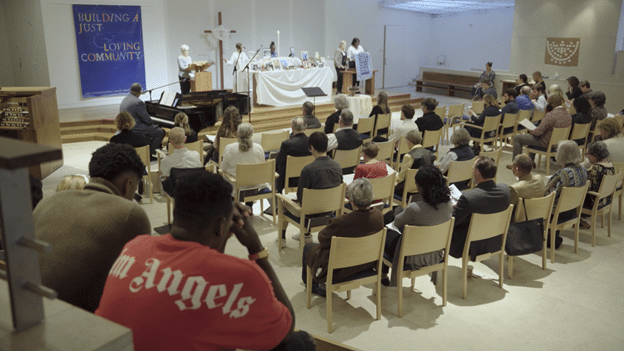

Last year’s All Saints Sunday was the first time that First Congregational United Church of Christ in Washington, D.C., spoke the names of the people who were enslaved on the land where the church now sits. It was once a tobacco plantation.

In the service, congregants were invited to offer photos of beloved people who had died, like they do at each year’s All Saints worship. But this time they also brought forward sacred items – clay marbles, tobacco, cotton – representative of the names called. These were prepared and blessed by artist Jessica Valoris.

“We invited people to come forward and take vials and place them up on the worship table to signify that these ancestors are joining the table of this cloud of witnesses, the table of our ancestors and our saints,” said the Rev. Amanda Hendler-Voss, senior minister of First Church.

First Church’s 2023 All Saints service is the focus of the short documentary film Speaking Their Names: Remembering the Enslaved People Who Worked This Land, edited by video journalist and church member Hannah Long-Higgins, together with director of photography Xinyan Yu.

The service and documentary mark a significant piece of First Church’s ongoing journey to excavate their hidden history. Hendler-Voss, together with Renee K. Harrison, associate professor of African American and U.S. religious history at Howard University, have previously shared some of First Church’s story of Excavating Hidden Histories: An Antiracist Practice of Healing through the UCC’s Join the Movement Toward Racial Justice.

‘A reclamation of sorts’

It was Harrison who ignited the church’s motivation to dig deeper into its history when she offered the keynote address at the church’s 150th anniversary celebration in 2015. She challenged congregants to engage with the land beyond the church’s recorded history and to ask what it means to do anti-racist work while worshipping on grounds that were formerly a tobacco plantation.

Long-time member Meg Maguire recalls this message as “a bit of a revelation because our history has always been told from the church’s founding in 1865 by abolitionists. That’s a great story, but it was sort of astounding how incomplete that story seemed.”

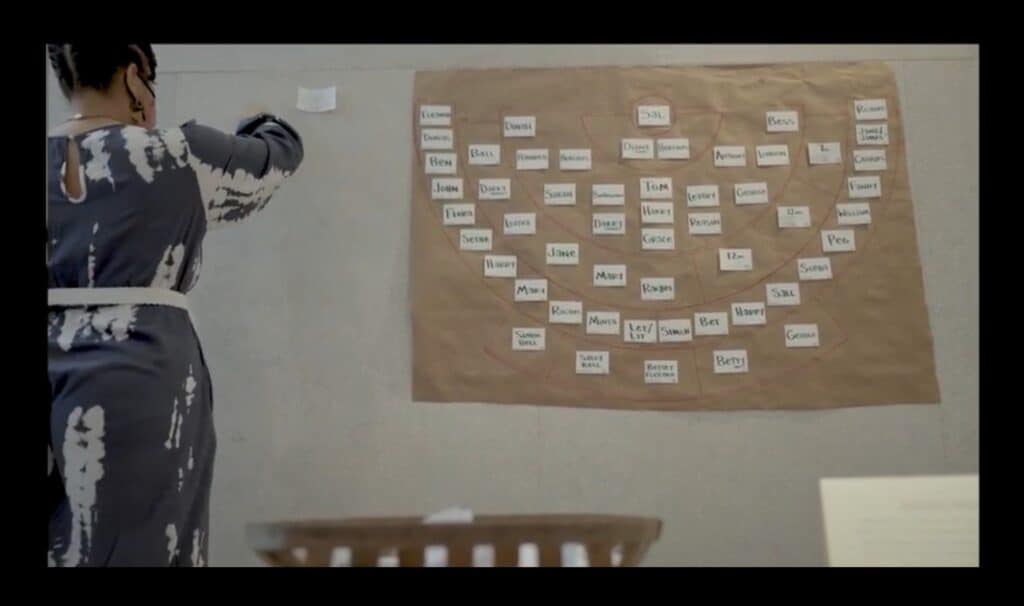

First Church is no stranger to documenting history. It hosts an archival room and archivist volunteer related to its location in the nation’s capital. So, First Church sought to dig deeper with the assistance of Howard University doctoral student Antonio Austin. He researched the Burns family, who owned a large amount of the property that became Washington, D.C., and, in government records, he found the names of people enslaved by the Burns family.

“This project is a reclamation of sorts,” said Austin. “The people here at First Church were and are interested in an unabridged history – something that is not whitewashed – and I think that, at times, you don’t find majority-white congregations and white people interested in addressing these types of uncomfortable truths.”

“We can’t be afraid or feel too fragile about our past. It is. We don’t change it, but we can understand it,” said Maguire. “By knowing these names through Antonio’s research, by having a list of names, we have a glimpse, but we don’t have their stories.”

‘Heart and body work’

“We’re in this moment where many are examining the history of institutions to tell a more nuanced story,” Hendler-Voss reflected. “There was a period where histories were told more triumphantly. In the UCC, we have the Amistad story. We’ve told the triumphalist story, but not the more nuanced story about roles we’ve played in harm and perpetuating racism and playing into internalized racial superiority in ways perhaps we never intended.”

She emphasized the importance of engaging history through creative and artistic mediums because “white supremacy has us in our heads, and we know anti-racism is heart and body work. The arts are able to bring us into that.”

First Church commissioned Valoris, who is a local D.C. artist, to accompany them in engaging with this piece of the church’s history. She led community conversations, deeply engaged with the names of the enslaved people, and is in the process of creating an artwork to be installed in the coming months.

Remembrance, evaluation, healing

Eight years after her initial challenge to dig deeper, Harrison has remained in relationship with the church and took part in leading the 2023 All Saints service. Hendler-Voss expressed gratitude for Harrison and described the importance of predominantly white congregations who are engaging in anti-racism work to have strong partnerships with institutions of color and accountability relationships with faith leaders of color.

“We leaned into the richness of Christian tradition around confession, lament, celebration, baptism water,” Hendler-Voss said. “A lot exists in our tradition that can spiritually equip us in anti-racism work, which is a lifelong journey, and activate the spiritual side of it.”

“As an act of grace, the First Church community worked to reclaim the church’s full history beyond a European and white American perspective and made way for the erection of a monument in their sanctuary as a means of remembrance, self and institutional evaluation, and healing,” Harrison said. “I have witnessed people from diverse backgrounds and cultures coming together to honor the contributions and sacrifices of Black people who were enslaved and forced to help build the nation’s capital. This willingness demonstrates their openness to go beyond themselves for the greater good.”

‘Make ripples’

The visual artwork that First Church will install, as well as the documentary, creates a record of the learning process that current and future generations can revisit.

“This is an unfolding. We’re changing our hearts and seeking to change the culture of an institution that’s existed since 1865,” said Hendler-Voss.

She hopes that documenting and sharing First Church’s story may help create connections and support with other congregations.

“Excavating the history and retelling the story with greater honesty, authenticity, and nuance is the project I hope that other congregations are also embarking on,” Hendler-Voss said. “As we’re doing that across the United Church of Christ, we benefit from hearing one another’s stories.”

The meaningful All Saints service closed with a benediction from Harrison: “Go forth in love, beautiful people, and continue to make ripples throughout the nation.”

Content on ucc.org is copyrighted by the National Setting of the United Church of Christ and may be only shared according to the guidelines outlined here.

Related News

Thompson to bring a ‘prophetic and pastoral’ message to Synod: ‘We are not all the same, but still one body’

On Sunday, July 13, the Rev. Dr. Karen Georgia Thompson will take the stage at the 35th...

Read MoreSend a prayer shawl along to General Synod 35

There’s been a buzz about Missouri, Kansas – can you hear it? It’s more of a clicking...

Read MoreOpinion: UCC pastor and former Institute of Peace Staffer calls for action in defense of peace

Editor’s Note: The United States Institute of Peace (USIP), an independent institute founded...

Read More