Fix systems that pandemic reveals are broken, Earth Day panelists urge

A national ministry of the United Church of Christ celebrated Earth Day’s 50th anniversary with calls to protect nurses, African Americans and poor people during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to fix food, health and other systems that have links to the environment – and are now revealed to be broken.

Those messages – ranging from a call for working-class empowerment to a reminder that big things start small and local – came from a U.S. senator, activists, a minister and a professor in a pair of one-hour webinars sponsored by UCC Environmental Ministries on Wednesday, April 22.

“An Epicenter of Change: Earth Day in Cleveland 50 Years Later” featured U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown and experts from the city where the denomination has its national offices: a leader of a nurses’ union, the director of an African American health care organization and a professor of public health. “The Earth is the Lord’s,” also sponsored by Interfaith Power & Light, featured the Rev. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr., a past director of the UCC Commission for Racial Justice, which produced the groundbreaking 1987 report, “Toxic Wastes and Race.”

Both webinars were recorded and can be viewed on the UCC YouTube channel or by clicking on the images at right.

Justice as today‘s Earth Day mission

Brown said one place where the environment, poverty and the coronavirus intersect is the economically challenged section of southeast Cleveland where he lives. Compared to other areas, it has higher levels of lead in homes and worse air, water and soil contamination. “We know in this neighborhood and neighborhoods like this, the rate of asthma is higher, and the rate of diabetes is higher,” he said. Its residents also tend to be hard-hit by COVID-19, he said.

Fighting for those people and “for environmental justice and economic justice” is today’s Earth Day mission, he said.

“That means rededicating ourselves, even with an administration in Washington that has taken us backwards from the progress we made,” Brown said. He cited recent rollbacks – some even implemented in the midst of the pandemic – in car-mileage standards and clean air and water laws. “We need you to stay involved, whether it’s the mercury and air toxins rule, or clean car standards or anything else that matters during this awful pandemic.” He urged “a restart when it comes to the environment, a restart when it comes to economic justice, a restart when it comes to help disparities.”

‘In every crisis is opportunity’

“Clearly we’re in the midst of an epic crisis, but in every crisis is opportunity,” said Michelle Mahon, an assistant director of National Nurses United, a union of registered nurses. Cleveland, she said, once had a network of effective community-organizing hubs that worked holistically on health care, education, labor advocacy and problems such as poverty and pollution. These were part of an international “settlement house” movement started by nurses and social workers. “Unfortunately, we’ve seen over the past century that these public health initiatives … have been commodified,” she said, with health care now “part of a vast industrial complex.”

“Nurses, unfortunately, are living this out in our basic fight for protective equipment,” Mahon said. Manufacturers of items that would protect nurses from COVID-19 have lobbied against federal use of the Defense Production Act to increase supply. Thus, advocates for health-care workers face fights against industry lobbyists that are similar to those faced by people advocating for environmental, racial and other forms of social justice. “All of our struggles are interlinked,” she said.

She encouraged not only immediate action – such as signing her union’s petition to Congress for protection of nurses – but also seeing the pandemic as an opportunity to break with the past. Environmentalists and all kinds of social activists, together, must “recognize that this is a working-class struggle, and we can build the power necessary to re-envision, reimagine and demand a better future,” Mahon said.

City life: an environmental ‘obstacle course’

“Nothing just happens, including the patterns of illness and deaths that we are witnessing,” said Yvonka Hall, executive director of the Northeast Ohio Black Health Coalition. “COVID-19 is not choosing blacks as victims; rather, the deadly virus is highlighting disparities that existed before its emergence.”

“African Americans have more of the circumstances that make it hard to survive in this pandemic,” Hall said, including “deep-rooted poverty, preexisting medical conditions, less access to health care, less stable employment, lack of transportation, and racial segregation.” She said African Americans often work in areas that risk exposure to the virus – as grocery cashiers and in the fields of health, personal care, food service and delivery services.

“African Americans have more of the circumstances that make it hard to survive in this pandemic,” Hall said, including “deep-rooted poverty, preexisting medical conditions, less access to health care, less stable employment, lack of transportation, and racial segregation.” She said African Americans often work in areas that risk exposure to the virus – as grocery cashiers and in the fields of health, personal care, food service and delivery services.

In addition, she said, “rollbacks of environmental polices have made life in urban America an obstacle course that includes dodging poor air quality, lack of green space, and lead paint.”

For the near term, Hall called for increased COVID-19 testing to show where intervention can help most. But for the long term, she asked, “Will we – civil society, government, business – learn any lessons this time around? Will we reevaluate what is important? Will we be innovative and find solutions to the current drivers of destruction?”

‘Put on new glasses’

“One of the great lessons offered by Mother Earth is our interdependence and adaptability,” said Dr. Darcy Freedman, professor of environmental health sciences at Case Western Reserve University. That will be needed, she said, “as we prepare for the next 50 years of sustainability and environmental justice” in light of “inequities that structure society in a manner such that the goods and benefits are not fairly distributed.”

She described a research project she and colleagues are working on in Cleveland, “mapping out the sometimes hard-to-see” forces acting on the urban food system – and advancing “nutrition equity” in neighborhoods suffering from decades of disinvestment. “The changes needed to undo these injustices will require us to put on new glasses so we can see the complex web of environmental injustice,” Freedman said.

“Now is an opportunity to look ahead,” she said. “The disruptions from COVID-19 weaken tried-and-true systems, and in so doing they provide a chance to envision and then begin to implement a new plan” – for example, for food supply chains that integrate environmental, employment, agricultural and other concerns. “COVID-19 illuminates how a change in one area will have an impact in so many others.”

“Imagine April 22, 2070, as a time when we celebrate the transformative power of a crisis that was used to ignite bold changes for environmental justice in Cleveland and beyond,” Freedman said. “We did this 50 years ago, and I look forward to joining with all of you as we bring this vision to life.”

‘You have to resist in real time’

Chavis said his involvement in what is now a worldwide environmental justice movement started with a local issue. In 1982, the UCC racial justice commission responded to a call for help in rural Warren County, N.C. “The governor had decided to dig a hole in the earth, and to place in that hole, which he called a landfill, in the middle of a Black community, some hazardous waste,” Chavis said. “The governor ordered that 60,000 tons of PCB – that cancer-causing polychlorinated byphenyl – be dumped in the pit.”

“Oh, my God,” he remembered thinking. “Of the 100 counties in North Carolina, why pick the poorest county? Why pick the most predominantly Black county?” Chavis organized citizen resistance. “I was so proud of the women, men and children of faith who laid down their bodies on the dusty roads of Warren County to resist, and to prevent the trucks that were heavy-laden with the PCBs from reaching the dump site,” he said. “Over 500 faith-filled, righteous protestors were arrested” – including him.

While he was in jail, the connections dawned on him. “At that moment,” Chavis said, “it was clear to me that environmental racism was real, and that that form of racism needed to be confronted and resisted, both by the civil rights movement and the environmental movement.”

Concrete, local responses to injustices can start larger movements, Chavis said. “I think the prophetic thing is not only to hear what God is saying, but to act on it. And this is where resistance comes. We have to resist the powers of evil in real time. You cannot procrastinate when it comes to resisting evil.”

Chavis said the current pandemic had not dampened his hope that movements for justice would continue. “Even amidst the contemporary suffering, preventable death, sorrow, pain, anxieties and worries as a result of COVID-19, there is the very real possibility in the providence of God that we will emerge out of this period of time with a greater sense and a deeper consciousness about the intersections between our faith and human health, global climate, and environmental justice and equity.”

Related News

Who’s Next?

This week the Supreme Court agreed to oral arguments on the challenges to Presidential...

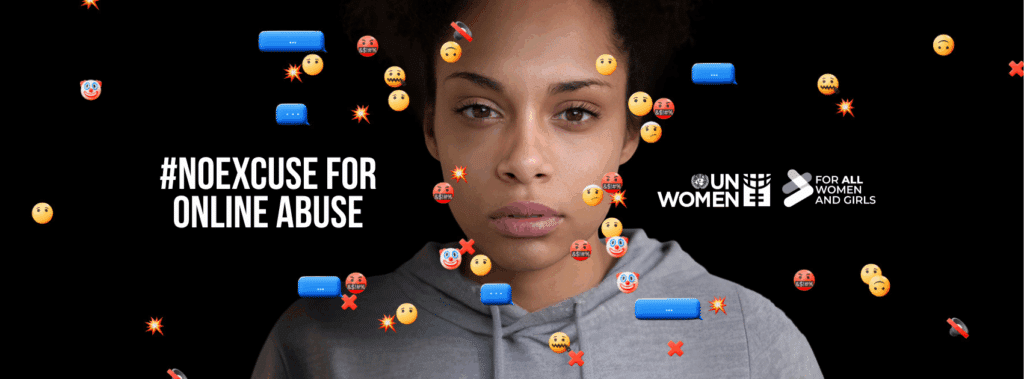

Read MoreGender and Sexuality Justice Ministries joins global movement to end violence against women, children

The Gender and Sexuality Justice Ministries (GSJM) of the United Church of Christ has joined...

Read MoreUCC and United Church of Canada celebrate a decade of ‘shared mission, mutual accountability, common hope in Christ’

Ten years ago, the United Church of Christ (UCC) and The United Church of Canada (UCCan)...

Read More