God is black with dreadlocks

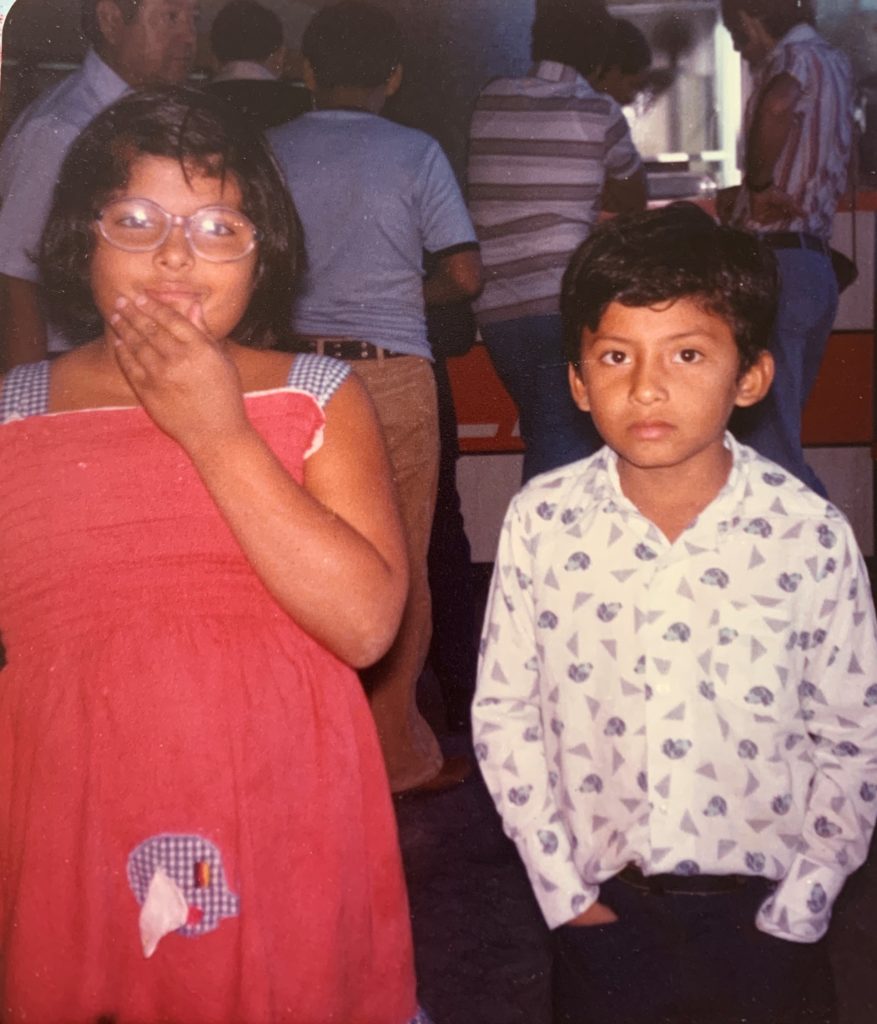

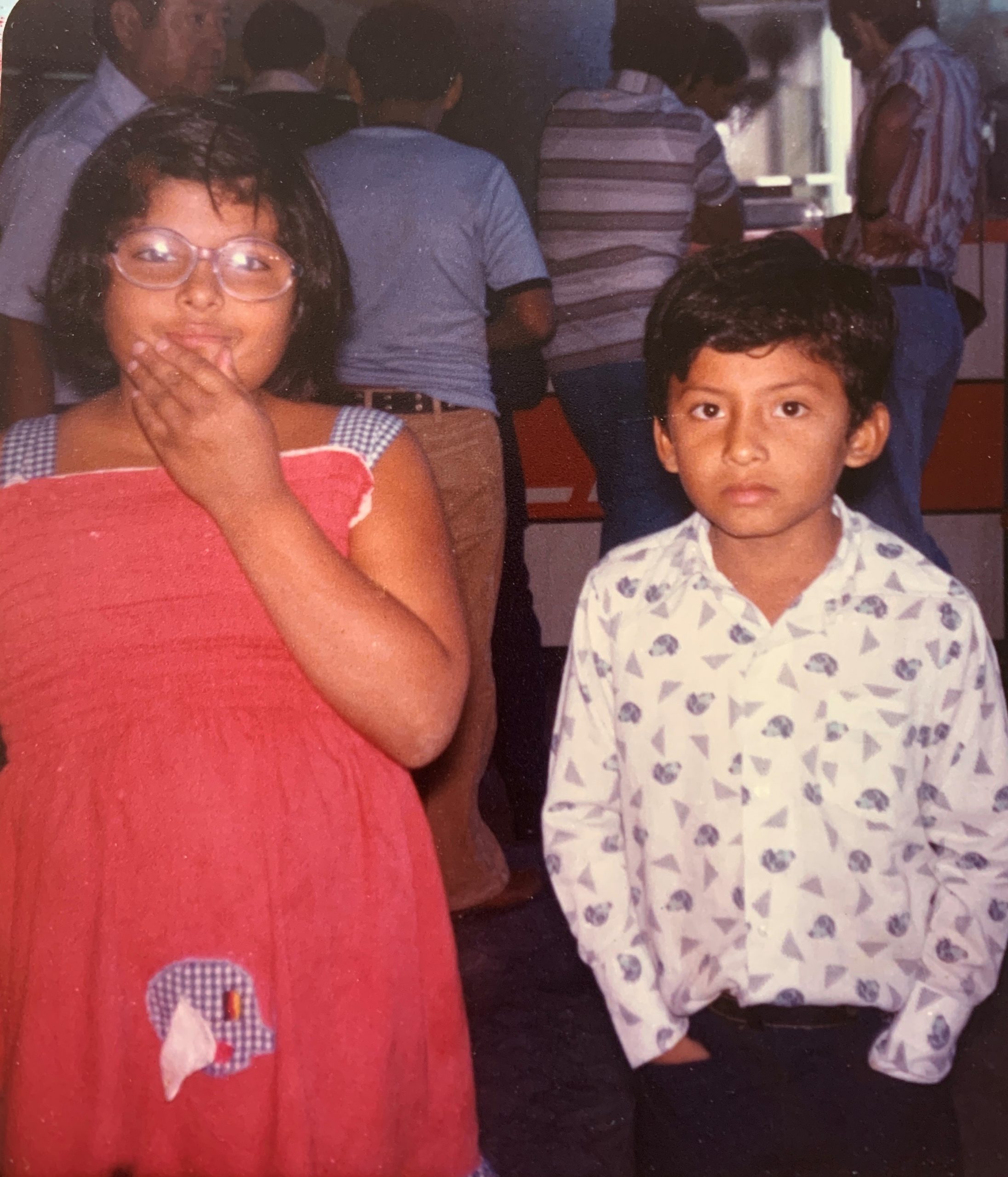

When I was ten, I was still living in El Salvador. My brown morenita’s skin used to get even darker when kissed by the Central American’s sun. A friend of my mother used to tease me calling me “Negrita” (Endearing Spanish for little black girl). In tears, I asked her to stop calling me “that.” Why? What was so insulting about it?

When I was ten, I was still living in El Salvador. My brown morenita’s skin used to get even darker when kissed by the Central American’s sun. A friend of my mother used to tease me calling me “Negrita” (Endearing Spanish for little black girl). In tears, I asked her to stop calling me “that.” Why? What was so insulting about it?

I was a teenager when my family and I moved to the US. We lived in Long Island, NY, in a very segregated neighborhood. “Black” took a totally different meaning. African-Americans were enemies to Latinxs especially newly arrived immigrants. We were told not to mess with Blacks in the school because they did not like us, and they would beat us. My aunt had been left unconscious in the street when she first arrived in the US by a couple of African-Americans who robbed her. The tension was real. My brother kept a baseball bat in his locker for those times when Latinx kids and African-Americans kids fought in school.

It was not until college when I started to cross racial boundaries and to speak English for that matter. I had been intimidated into speaking my accented broken English in High School because ignorant teachers mocked me, and so if I could, I avoided speaking English in public. I also began learning about the cruel history of African slave trade and segregation. This type of history was never taught to me in El Salvador. In the same way we don’t learn that Maximiliano Martinez, a Salvadoran president of indigenous descent, massacred 32,000 indigenous people in 1932. In all of my self-hatred, I also struggled with my own culture’s legacy of anti-blackness.

Where do we start healing from the white devil supremacy? I know for me; it has been a long life journey that is still not complete. When I started working for a national non-profit advocating for LGBTQI kids, my world expanded. Young people mostly brown and black started teaching me why our struggle couldn’t be separate. They taught me that the sum of all of us is better than being clustered into our own different corners. It was in those forums where I began finding strong Black women taught me that fighting for dignity is fighting for dignity. Up until then, I had racialized anger into an act of aggression, a threat. A Black colleague with dreadlocks, Mustafa Sullivan, recited the most beautiful poetry at a work event:

“Every 28 hours

Every 20 hours

Every 8 hours

Another black mother loses

Her son in this

Alleged Jesus nation

Where people forget

That we are black love

And revolution is a time

When god speaks”

When I got home I told my wife “I think God is black with dreadlocks.”

My healing from anti-blackness is still in the making. It started when I acknowleded that I too have been blind to the marginalization of my Black siblings. It began when I accepted that I too perpetrate oppression when I stereotype black people in order to feel better about being an immigrant. Healing the wounds of white supremacy is a divine journey against the rooted notion that our Black siblings are not inherently good. From the beginning of their arrival in the American continent, they were seen as soulless and not human. Slave masters didn’t want to teach Christianity to them because they didn’t think it was important to baptize them. However, when they found it economically advantageous to convert them to Christianity to guarantee their submission, they started teaching them about Jesus. What the oppressor didn’t know is that teaching the “the way, the truth, and the life” calls for liberation.

Dear Diosa, help us to renew ourselves with the understanding that God is bigger, colorful more encompassing that our minds can comprehend.

Related News

UCC celebrates Womxn’s History Month in March and beyond

Womxn's History Month is designated in March, and the United Church of Christ is celebrating....

Read MoreFive years later: How did the Covid-19 pandemic impact ministry?

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared Covid-19 a global...

Read MoreRev. Shari Prestemon nominated to serve as UCC’s Associate General Minister and Co-Executive, Global Ministries for Love of Neighbor Ministries

Re-entering the room at the March 2025 UCC Board Meeting in Cleveland to a standing ovation,...

Read More