Keynoter Valarie Kaur challenges UCC to chart a ‘revolutionary love’

In her keynote address to the 33rd General Synod July 12, social justice activist Valarie Kaur provided the United Church of Christ with a “compass” that she urged every one of its congregations to use to become a “pocket of revolutionary love.”

Kaur stressed that in light of the demographic changes now taking place in the United States, “we have 25 years” in which to “transition this nation into a multi-racial democracy…” She asked, “Will we continue to teeter on the brink of civil war…or will we begin to birth a nation that has never been…”

“You have the resources to strengthen the beloved community you already have,” she told her virtual audience in a live presentation that concluded with a question-and-answer session. “Revolutions happen in those spaces where people are coming together to inhabit a new way of being, and that is what the UCC is.”

Kaur’s speech embodied key components of her approach to building the beloved community. She began by urging her audience to take deep breaths and to remember the resilience and wisdom of their ancestors. She recited a litany of crises the world now faces—a global pandemic, climate change and wildfires, a racial reckoning, battles over voting rights—but she said, “your breathlessness is not your weakness. It is a sign of your bravery.”

She then described how she had gotten to know UCC leaders and saw how the UCC “marries love and service.” Kaur recounted how she had first worked with “a phenomenal force,” Cheryl Leanza, the public policy director of the denomination’s media justice ministry, OC INC., on the Faithful Internet initiative in support of equitable access to the internet. She described how she was “inspired” when she spoke to a meeting of the Southern New England Conference and discovered “a community that could take hands with a Sikh sister.” The Rocky Mountain Conference then invited her to talk about her book, “See No Stranger: A Memoir and Manifesto of Revolutionary Love.” But “perhaps nothing has been more life-giving,” she recalled, than her growing friendship with Associate General Minister Traci Blackmon, whom she met at Rev. William Barber’s “Watch Night” service. “She has shown up for me as a sister, again and again.”

Building ties through stories

Kaur then connected with her listeners by describing the key moments of her life that had shaped her approach to pursuing Revolutionary Love. She shared how she had grown up in a Sikh family that had farmed in California for generations. She recalled her grief and anger when a close family friend, Balbir Singh Sodhi, whom she called “Balbir Uncle,” was murdered in Phoenix shortly after 9/11, becoming the first victim of the hate crimes that occurred in the wake of the attack by someone who thought he could show he was “a patriot” by killing someone who had a beard and wore a turban. But that moment, she said, had galvanized her to go to both law school and divinity school. She began to try to effect change for social justice.

Kaur then described the recent terror she had experienced on January 6, when she learned that her brother-in-law, a CNN reporter, was trapped inside the U.S. Capitol when the insurrection broke out. “I could only imagine what they would do if they found him,” she recalled. “Not only a reporter, but a brown man.” Only after she knew her family member was safe did Kaur become aware of her body and how shaken it felt. “This is terror,” she thought, “and the terror is familiar. For how many times in the last 20 years have I seen people I love, in the face of white supremacism and violence, and felt unable, helpless to protect them?”

Kaur said she then realized there was “an absolute through-line” between 9/11 and January 6—“the story of a country that clings to the ‘us and them’ narrative.”

But that same day, she said, she received a phone call from one of her closest “teammates” at the Revolutionary Love Project that Kaur had founded. The woman shared that her parents were outside the Capitol, praying in support of the protests. And Kaur said, “As much as I wanted to hate those people. … I had to see them through the eyes of their daughter, who saw them not as evil, but as deeply wounded. As frail human beings, who did not know what else to do with their pain, their confusion, their own impulses to hate and turn the gun on us.”

Kaur said that her friend saw the protestors as parents she wished that she could help. “That does not make them any less dangerous,” Kaur observed, “but it does release their power over us. When we choose to see our opponents not as monstrous, but as wounded human beings, it releases their power over us.”

‘Revolutionary Love’ compass

Having captured the attention of her Synod audience, Kaur then moved to on to consider what she called “the question of the hour: Why build a world rooted in love? Why declare a revolutionary love the call of our time? Because,” she explained, “there’s no other way to transition. …You are here tonight because you know the crises we face are not just social or political. They are spiritual.”

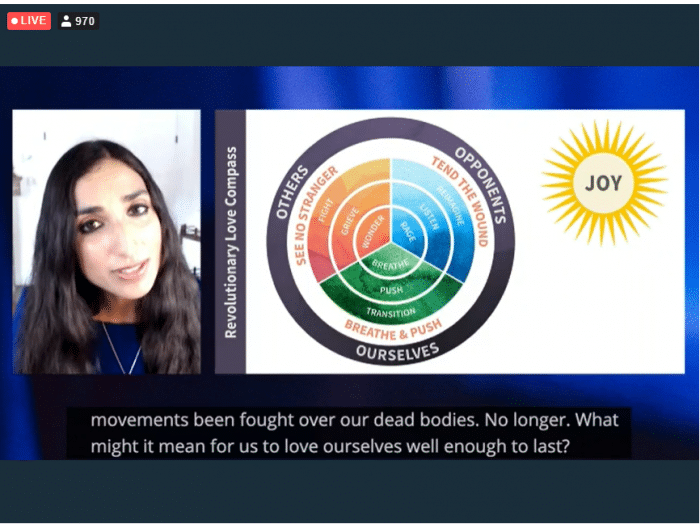

Kaur then described the 10 practices of her Revolutionary Love vision as points on a compass that can be directed to anyone—others, opponents, or ourselves—who is in need of love.

For “Others,” Kaur urged the practice of what she called “See No Stranger.” First comes wonder, realizing that we have to learn to see others differently than our usual stereotypes. She observed that that kind of love has “always been disruptive,” and pointed to the ways views began to change when people could see the world through the eyes of George Floyd, Brianna Taylor or refugee children incarcerated at the border. Then she said it is necessary to grieve with others. After that, you can learn to fight on their behalf.

Turning to “Opponents,” she said the process begins with rage, but the solution, she said, “is to process rage in safe containers. We need the singing, dancing, drumming, wailing and shaking. We need to be with others who can help us. …” When we are safe enough to listen to our opponents, she said, the goal is simply to understand them. Reconciliation and transformation may come, she added, but if it doesn’t, that’s still okay. The third stage is to move from resistance to reimagining, and to become aware of the wounds that drive your opponents.

Kaur said that 15 years after Balbir Uncle was murdered, she reached out to his killer in prison. “It was so hard,” she remembered. “But it began a process of reconciliation.” Kaur said she now meets with the man every few weeks “and I read him from my book!” She said she can “see the wound in him” and can understand that “so much of white supremacist aggression is unresolved grief.” But she cautioned her listeners, “Just remember that it took me 15 years. … Some of us need to stay in the grief and rage and let others do the work. … I could let go. It was burdening me.”

“If you are someone who has a knee on your neck right now, it is not necessarily your role to look up at your opponent and try to wonder about them,” she said. “Your role … is to take the next breath. But if you are someone who is safe enough, … we need you.”

Breathing, then pushing

Finally Kaur said, “the only way to sustain yourself in any long labor is not to forget how to love ourselves.” Kaur described this as “the feminist intervention,” and added, “this is where I reach for the wisdom of the midwife,” who reminds a woman in labor to breathe and then to push. “I want to grow old with you,” she told her audience. “I want to last and I want you to last. These practices about breathing, and pushing and summoning the support and the wisdom to transition, that is how we practice loving ourselves.”

Finally, she said, all of this must be done with joy. “Even in darkness,” she said, “even in the pain of labor… when I am doing (it) in community, it makes space to let joy in.”

“In any given season of our life,” she said, there is one of these approaches “we need more than any other.” Then she challenged her audience by asking, “What do you need? … What does your congregation need?”

“I have found that the work for justice has gone on long before we were born, and it will continue long after we die. … There will still be labor for our children to do.”

At the end of her address, she invited her audience to “breathe and then to push, for this is not only a time of transition, it is a time of rebirth.”

Unlike every Synod keynote address before hers, Kaur spoke from a small room in a house, rather than from a podium in a cavernous convention hall. But in this case, the virtual format may have made her message even more powerful, as her emotion and passion were easier to experience for those watching on computer screens from the intimacy of their own homes.

When she was asked after her formal talk what needed to be done next, Kaur noted that this year will mark the 20th anniversary of 9/11. “It is time to do the thing you have not yet done … to build the Beloved Community right where you are.”

Kaur is now building “The Learning Hub,” a collection of resources to help persons understand this approach, which is available here. Some congregations are helping her develop the resources. More about her approach is detailed in her 2020 book, “See No Stranger,” which is available here.

Sara Fitzgerald, a General Synod Newsroom volunteer, is a member of Rock Spring Congregational UCC, in Arlington, Va.

Related News

A Moment of Silence

The weekend news was alarming. Two students shot and killed with 9 injured at Brown University...

Read MoreIn hope-filled worship service, UCC and United Church of Canada celebrate full communion past and future

On Saturday, Dec. 13, many from the United Church of Christ (UCC) and the United Church of...

Read More‘A Gift of God to the World:’ Christmas greetings from the General Minister and President

As Christmas quickly approaches, UCC General Minister and President/CEO the Rev. Karen Georgia...

Read More