UCC encourages churches to respond to rise in US overdose deaths

With people dying from drug overdoses at a record rate nationwide, a United Church of Christ ministry is working to save lives — and change minds.

Local churches have important roles to play in the effort, said Erica Poellot, who coordinates the UCC’s Harm Reduction and Overdose Prevention Ministries. To get more congregations involved, the ministry is inviting people to two webinars:

- A “Blue Christmas Service,” Thursday, Dec. 16, at 3:30 p.m. ET, co-produced with the UCC Mental Health Network. People can see a description and register here to view the prerecorded service and interact live with others via Zoom’s chat feature. The service, which originally aired in 2020, can also be viewed anytime at the UCC YouTube channel.

- A “UCC Substance Use and Overdose Town Hall,” Wednesday, Feb. 2, at 6 p.m. ET. Interested people can email Poellot to receive updates or watch the “Events” page at ucc.org for a registration link to be posted.

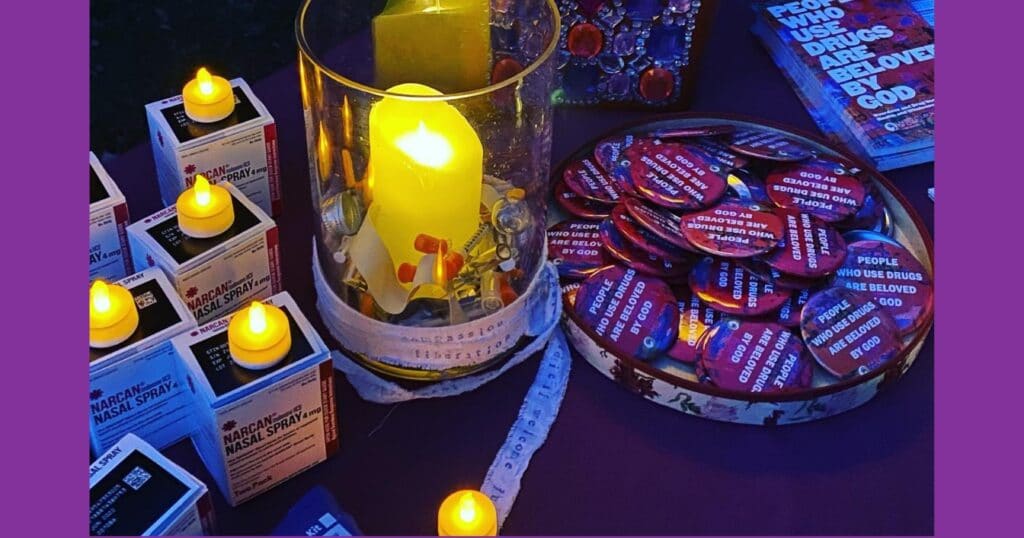

She said both will offer glimpses into harm-reduction work and its core message: “People who use drugs are beloved by God.” And with the current uptick in deaths, there’s never been a more urgent time. A recent report from the National Center for Health Statistics showed that, for the first time, drug overdose deaths topped 100,000 in a year.

Why more are dying

There are complex reasons for the rise in deaths. One of them, Poellot said, is “a toxic, unpredictable and unregulated drug supply in the U.S.” Cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin and other drugs are now often “cut” with fentanyl, a synthetic and often deadly opioid. She said fentanyl is “similar to morphine but 50 to 100 times more potent” and “can be produced for a significantly lower cost.”

Just as important, though, are problems in the way drug use is talked about and punished. In the U.S., stigma and criminalization make everything else worse, Poellot said.

“Common vernacular says we are engaged in a war on drugs,” she said. “Yet the war is actually a war on people, and most specifically a war on poor people, Black and brown people, pregnant and parenting people, LGBTQIA+ people, people made vulnerable by immigration status, and so forth.”

Why stigma doesn’t help

The focus on crime makes it harder for people “to keep themselves safe,” she said. “It limits access to social support, connection and compassionate and quality care.” She gave these examples of how this affects people who use drugs and those who love them:

- “You cannot tell emergency medical services that a person is overdosing. You need to say instead that they are not breathing, not conscious, knowing that in many areas EMS will respond slower to an overdose.”

- “Not being able to get a job, even among our mainline denominations, unless you can prove that you are abstinent from all drugs that have been deemed socially unacceptable or illegal.”

- “Your urine being used to determine if you are a capable and loving parent.”

- “Over 97,000 people dying last year alone because they could not access the life-saving, life-giving resources they needed to be able to keep themselves safe.”

“The dominant narrative is that substance use, and substance use disorder, are a matter of pathology and criminality. We respond accordingly by stigmatizing and incarcerating people who use drugs.” This, she said, leads “to increased marginalization and isolation, and to violence, entrenched poverty, and trauma.”

Stigma, she said, “is the core driver of harm for people who use drugs and their loved ones and communities.” And that is where the church and other compassionate allies can help.

What churches can do

Poellot gave these as examples of local work recently done by UCC churches and leaders:

- High Country UCC in Vilas, N.C., connected over the summer with Olive Branch Ministry, a regional, faith-based harm-reduction nonprofit, for a donation drive and a Sunday sermon titled “God’s Doors are Open to All People Who Use Drugs.”

- Orient (N.Y.) Congregational Church held a Sept. 23 community conversation, “Spirituality in Light of Substance Use,” on approaches to harm reduction on Long Island.

- The Penn West Conference made harm reduction and substance use the focus of its annual spring clergy-ethics retreat.

- Empowerment Liberation Cathedral in Washington, D.C., held a March 18 training in how to use naloxone to help a person recover from an opioid overdose.

- In Orono, Maine, UCC minister Malcolm Himschoot brought harm-reduction activist Blyth Barnow to the nondenominational church he serves for a harm-reduction service in August — and connected with a local agency to obtain naloxone for the church.

Naloxone, also known by brand names such as Narcan and Nevzio, offers an easy first step in harm reduction for many churches. Poellot said she recommends churches “make sure all clergy, staff and parishioners have access to naloxone and know how to use it.” “Normalize naloxone possession as an essential medication,” she urged. “Destigmatize its use.”

A naloxone maker, Emergent Bio, donated some to the UCC this year. In the face of a recent shortage, Poellot said her ministry has been getting it out to “people who use drugs, and faith partners, across the country where access is very limited and overdose rates are disproportionately high.” West Virginia, Indiana, Ohio and Tennessee are among those areas. “Over the past 18 months we have distributed over $75,000 worth of Narcan for free to people at risk of overdose.”

Signs of hope

At the federal level, there is some hope for a more humane approach to people whose drugs, Poellot said. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released an overdose prevention strategy in October. And on Dec. 8, its Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration backed that up. It opened an application process for $30 million in grants for harm reduction, made possible by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

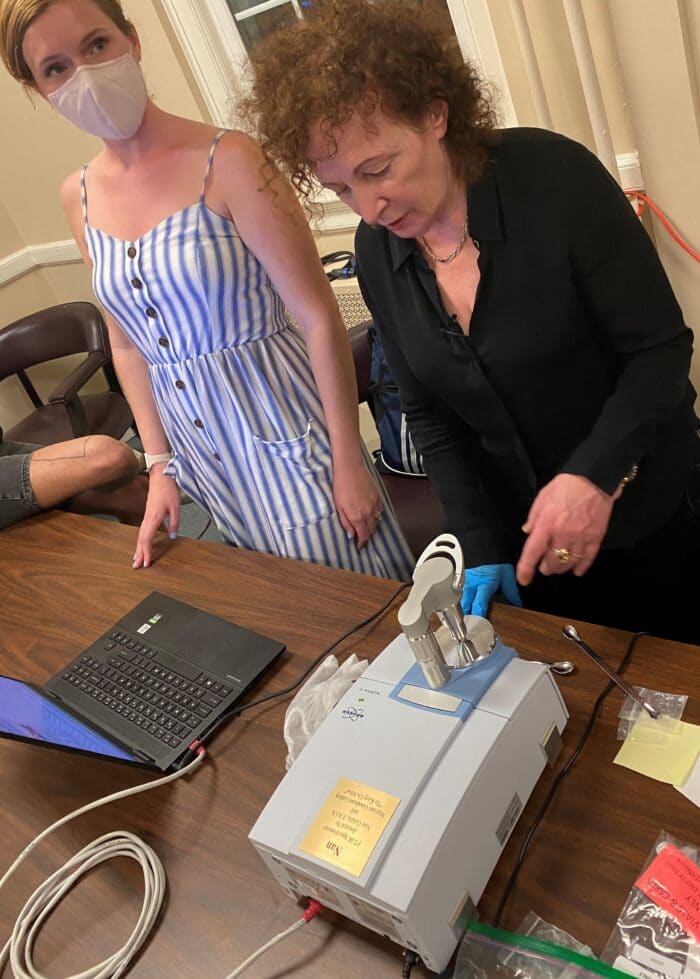

Churches can push for good local laws, too, she said: “Advocate in your city, county or state for access to non-coercive, evidence-based treatment.” This, she said, can include access to naloxone, fentanyl test strips and drug-checking technology. In August, she took part in the blessing of a machine operated by the North Carolina Survivors Union that helps people check substances for fentanyl.

Poellot said she hopes churches will lead efforts to create overdose prevention centers that offer such resources — something other countries have long had. “New York City opened the first legally sanctioned one in the U.S. this month,” she said. “There were nine overdoses in the first four days and zero deaths. There has never been an overdose fatality at an overdose prevention center, despite millions and millions of uses of substances by people at these locations.”

‘Where the magic happens’

And there is much else congregations can do, Poellot said. She invited people to:

- Contact her “to help you develop an overdose response plan for your congregation and obtain naloxone.”

- Use “Spirit of Harm Reduction: A Toolkit for Communities of Faith Confronting Overdose” with a church discussion group.

- “Challenge the stigmatization of substance use by using stigma-free language to talk about the issue.”

- “Hold a harm reduction supply drive for a local harm reduction organization.”

- “Hold a conversation series or listening session on overdose and substance use in your congregation or community.”

- “Hold an awareness event and service of remembrance on International Overdose Awareness Day” next August.

- “Preach and teach on the stigma of substance use.”

- “Post local harm reduction, mutual aid, and other evidence-based treatment resources in your church.”

- “Donate to UCC Harm Reduction and Overdose Prevention Ministries.”

Local churches, she said, have spiritual tools for all of that. “It is about working to examine and revision the language we use to talk about people who use drugs, understanding the power of naming to harm or to heal.”

The challenge is “to examine the many ways we have institutionalized the othering and dehumanizing of people who use drugs, and being willing to co-create new ones in partnership with people,” she said. “And most importantly it is about tearing down barriers to connection, and returning people to community, understanding that community is where the healing, the magic, the life-giving happens.”

Related News

Send a prayer shawl along to General Synod 35

There’s been a buzz about Missouri, Kansas – can you hear it? It’s more of a clicking...

Read MoreOpinion: UCC pastor and former Institute of Peace Staffer calls for action in defense of peace

Editor’s Note: The United States Institute of Peace (USIP), an independent institute founded...

Read MorePension Boards appoints David A. Klassen as its President, CEO

The Pension Boards, an affiliated ministry of the United Church of Christ recently announced its...

Read More